Estimated at approximately 700,000 adults and children in the UK (1/100), autism spectrum disorder (ASD) affects a large proportion of our population. Alongside characteristic symptoms, individuals also often present difficulties with emotional regulation (ER) 1.

Difficulties with Emotional Regulation in ASD

Impairments in ER often present as meltdowns/uncontrolled outbursts, shutdowns, impulsivity, irritability & extreme anxiety. Much of this research has focused on children and young adults, often resulting in increased use of future psychiatric services, compared to those without ASD2.

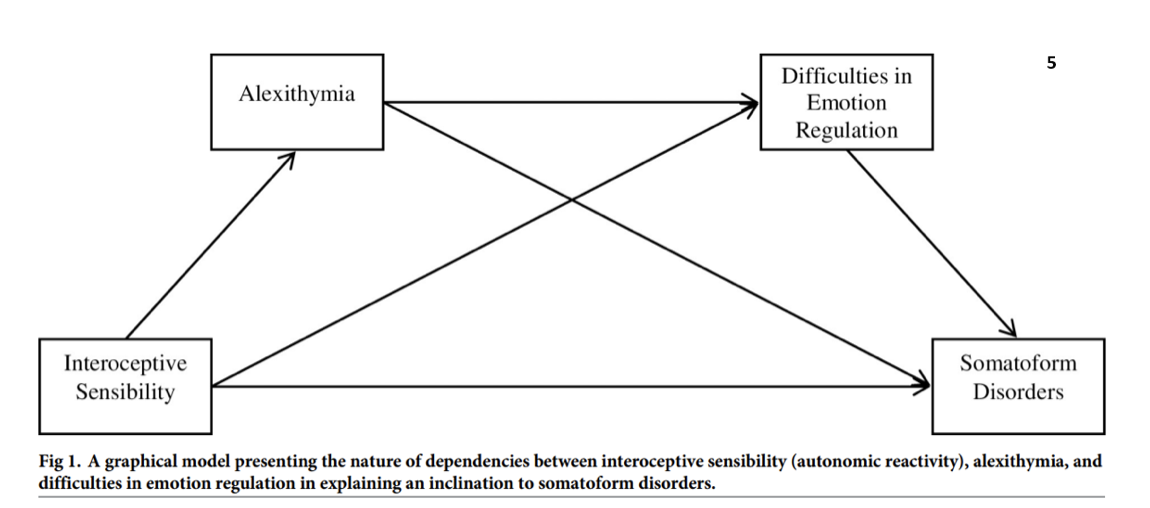

This may be the result of adopting maladaptive ER strategies, such as suppression, rumination, and avoidance, paired with reduced use of adaptive strategies, such as reappraisal and affect labelling3. Further to this, individuals often report increased difficulties with identifying and describing their emotions, a phenomenon known as emotional blindness or alexithymia4. Such difficulties may be partially explained by differences in both perception and information processing, contributing to altered interoceptive sensibility and in some cases the presence of somatoform disorders also5.

A supporting model posits that both alexithymia and ER mediate the relationship between autistic symptoms and poor mental health (namely symptoms of depression and anxiety)6. The presence of alexithymia, estimated to be as high as 60% in ASD7, has been demonstrated in both high and low functioning individuals, with the added factor of non-verbality increasing alexithymia severity8. Investigating gender differences, research has shown females with ASD to have more severe dysregulation compared to males9,10, an element to be considered in upcoming research.

In terms of neurobiology, altered prefrontal cortex-amygdala connectivity contributes to ER deficits, and as a result alexithymia. The nature of these alterations is still within question, be it hyper- or hypo-activation, but nonetheless altered neural connectivity in ASD is confirmed2.

The Science Behind Verenigma – Cognitive Reappraisal & Affect Labelling

It is well established that ER can be improved using cognitive reappraisal and affect labelling, decreasing alexithymia severity through a reduction of avoidance behaviours11. These techniques correct altered neuronal connectivity in limbic and prefrontal brain regions, targeting issues of poor interoception, emotional dysregulation and alexithymia12.

Cognitive reappraisal involves identifying and transforming negative thought patterns into positive ones. This process of self-reflection and reframing goes hand in hand with affect labelling, putting your feelings into words. This works to form a bridge between our emotions and our thoughts, allowing us to be more aware and in tune with ourselves.

With these techniques implemented within Verenigma, repeated use increases emotional wellbeing and eases psychological burden. Verenigma uses voice-emotion recognition technology to detect levels of anxiety, stress and depression. Upon recording voice notes, you are provided with a clear, real-time visualisation of your emotional wellbeing, promoting self-regulation and management.

Our Work To Date

In a recent study, we analysed the ability of Verenigma to decrease emotional volatility between individuals with ASD who regularly used Verenigma (>2/week) (n=46) and those who did not (<2/week) (n=37).

To measure levels of ER, we used the ‘Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale’ (DERS-16), which has 6 subdomains: non-acceptance of emotional responses, difficulty engaging in goal-directed behaviour, impulse control difficulties, lack of emotional awareness, limited access to ER strategies and lack of emotional clarity. Our previous work has shown a high correlation between emotional clarity and alexithymia, for which we used the ‘Toronto-Alexithymia Scale’, focusing on the differences in identifying emotions subdomain (TAS-DIF).

After using Verenigma for a month, the results clearly indicated the group with higher usage to have a smaller range in TAS-DIF (6.03 vs. 9) and DERS-16 (11.7 vs. 16) scores, demonstrating increased Verenigma usage to be associated with increased emotional stability. Furthermore, 58% of participants demonstrated a reduction in alexithymia severity.

Future Work – The Use of Verenigma in ASD

Decreasing emotional volatility through using Verenigma is a vital tool that can be implemented with ease into the lives of those with ASD. Aiding in self-management of one’s mental state, and thus reducing the onset/further development of mental health disorders, Verenigma is the way forward. Verenigma is the route to improving quality of life for patients and their carers’, reducing both hospitalisations and healthcare costs, generating enhanced wellbeing for all.

In light of this, we would like to propose the development of a pilot study to assess the efficacy and usability of Verenigma in a group of young people with ASD and learning difficulties, who may be at risk of hospitalisation. As a means to improve self-regulation, we wish to assess both efficacy in improving emotional regulation in this cohort and user experience of Verenigma. This will allow us to formulate a plan for potential integration of Verenigma within healthcare services, providing an alternative, non-pharmacological treatment route for improving emotional regulation in ASD.

References

- National Autistic Society. (2024). What Is Autism? Autism.org.uk; National Autistic Society. https://www.autism.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/what-is-autism

- Mazefsky. C. A., Herrington, J., Siegel, M., Scarpa, A., Maddox, B. B., Scahill, L., & White, S. W. (2013). The role of emotion regulation in autism spectrum disorder. Journal of American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 52(7): 679-88. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.05.006.

- Mazefsky, C. A., & White, S. W. (2014) Emotion regulation: concepts & practice in autism spectrum disorder. Child & Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 23(1): 15-24. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2013.07.002.

- Samson, A. C., Huber, O., & Gross, J. J. (2012). Emotion regulation in Asperger's syndrome and high-functioning autism. Emotion. 12(4): 659–665. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027975

- Zdankiewicz-Ścigała, E., Ścigała, D., Sikora, J., Kwaterniak, W., & Longobardi, C. (2021) Relationship between interoceptive sensibility and somatoform disorders in adults with autism spectrum traits. The mediating role of alexithymia and emotional dysregulation. PLoS ONE. 16(8): e0255460. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255460

- Morie, K. P., Jackson, S., Zhai, Z. W., Potenza, M. N., & Dritschel, B. (2019). Mood Disorders in High-Functioning Autism: The Importance of Alexithymia and Emotional Regulation. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders. 49(7): 2935-2945. doi: 10.1007/s10803-019-04020-1.

- Kinnaird, E., Stewart, C., & Tchanturia, K. (2019) Investigating alexithymia in autism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Psychiatry. 55: 80-89. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.09.004.

- Poquérusse, J., Pastore, L., Dellantonio, S., & Esposito, G. (2018). Alexithymia and Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Complex Relationship. Frontiers in Psychology. 9: 1196. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01196.

- Wieckowski, A. T., Luallin, S., Pan, Z., Righi, G., Gabriels, R. L., & Mazefsky, C. (2020). Gender Differences in Emotion Dysregulation in an Autism Inpatient Psychiatric Sample. Autism Research. 13(8): 1343-1348. doi: 10.1002/aur.2295.

- Mahendiran, T., Dupuis, A., Crosbie, J., Georgiades, S., Kelley, E., Liu, X., Nicolson, R., Schachar, R., Anagnostou, E., & Brian, J. (2019). Sex Differences in Social Adaptive Function in Autism Spectrum Disorder and Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 10: 607. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00607.

- Braunstein, L. M., Gross, J. J., & Ochsner, K. N. (2017). Explicit and implicit emotion regulation: a multi-level framework. Social Cognitive & Affective Neuroscience.12(10): 1545-1557. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsx096.

- Torre, J. B., & Lieberman, M. D. (2018). Putting feelings into words: Affect labelling as implicit emotion regulation. Emotion Review. 10(2): 116–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073917742706).